Zoma Museum: Addis Ababa’s urban escape into nature

This green oasis sits just a few miles from the centre of Ethiopia’s capital, championing art and sustainable architecture

When you think of a museum, what comes to mind? A sterile white room punctuated by sculptures on pedestals, perhaps. Or maybe a grandiose building filled with oil paintings in gold frames and trinkets from bygone eras. Zoma Museum in the Mekanisa district of the Ethiopian capital, Addis Ababa, is a far cry from any such institution. In fact, it’s so different that it’s rather hard to describe.

Zoma is no ordinary museum

Set away from the sprawling residences and concrete blocks that are starting to envelop Addis, Zoma is a verdant oasis consisting of an earthen art gallery, a restaurant, a circus school, a primary school, a library, an organic garden. It’s an urban escape. “You don’t just come here to look at art – the whole thing is art. We use the land as a canvas and paint it with green,” co-founder Meskerem Assegued tells me as she sits in the gardens, near-engulfed in some towering ginger plants.

It’s Assegued, an anthropologist and art curator, along with acclaimed artist Elias Sime who are responsible for this sustainable haven. They spent nearly two decades getting it to where it is now, including four years building and countless amounts of money funding it themselves. It truly is a labour of love.

The pair began collaborating back in 2002, when they set up the Zoma Contemporary Art Centre. Some 11 years later, after a great struggle to find somewhere suitable that they could afford, Assegued and Sime managed to expand by buying a stretch of land near the Old Airport (the now widespread nickname given to a Mekanisa neighbourhood near the decommissioned Lideta Airport). The former farming plot was abused and abandoned, and it took a lot of work to repair the land and ready it for growing plants without pesticides.

Co-founders Elias Sime and Meskerem Assegued

Creating the buildings for the gallery was a feat as well. Assegued was set on constructing them out of mud using a centuries-old vernacular tradition she’d discovered on her anthropological travels around Ethiopia. It was near-impossible for them to obtain a permit to create something new from these materials, so they built on what was already there.

Inspired by the ancient technique of chika (essentially wattle and daub), they built a bamboo frame and created walls from a blend of mud and straw, mixed every three days until fermented and gooey. It was at this stage that Sime used the earthen walls to sculpt patterns based on culturally significant Ethiopian events and ideas. One includes the ancient Ethiopian language Ge’ez, considered by some as the oldest in the world. Each wall, each building, tells a story.

Art is just one element of Zoma

“The public became very interested. People came to see Zoma before we even opened. It surprised them what could be made from this once-polluted land; how the earth can respond when you clean it up and use it properly,” says Assegued. “It was an advocacy to show people that you can change your city or your country or even the world into something green.”

And that’s exactly what sets this museum apart: it stands for something. Even when they come up against hurdles, Assegued and Sime persevere to do things the way they believe they should be done. Nothing is done by halves; there’s meaning behind everything at Zoma. It’s activism in museum form.

“We believe you have to be friends with the natural world. It’s not even a choice, really – it’s a survival issue.”

This is particularly evident in the educational opportunities it provides. For creatives, there’s an artist in residency programme that gives local and international artists the chance to live in harmony with nature, experiment with their craft, and “find alternative, artistic and creative solutions to environmental problems”. For young minds, there’s an open-air theatre, circus school (tightrope lessons, anyone?) and a primary school.

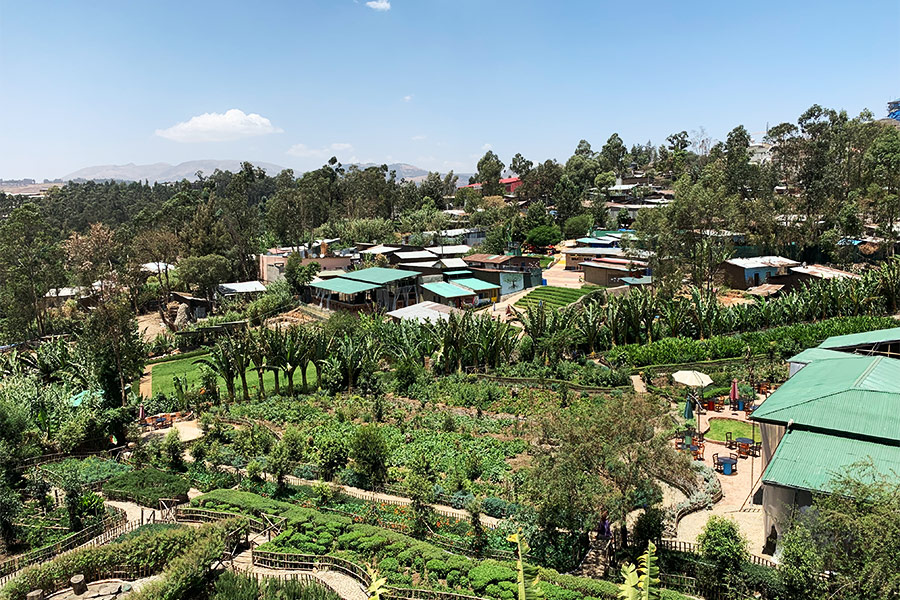

The view from part of the museum's extensive grounds

According to Assegued, it’s a mix between Montessori, Waldorf, Alice Waters’ Edible Schoolyard Project and the Ethiopian religious schools that go back thousands of years. Whatever way you describe it, it’s essentially hands-on learning. There’s a kitchen where the students learn to cook while simultaneously mastering maths and science. There’s a garden where they grow plants and relate them to language, science and social studies. There’s a computer lab where they discover technology. What seems to be most important to Assegued, though, is that all the students learn together.

“We have mixed education. That means children of different ages, genders and abilities are all in the same class. We also have students with what you might call ‘learning difficulties’, but we refuse to use that term. We just call [the students] by their names, like everyone else,” she explains. “I hate the idea of segregation and separating people because of this or that. I’m totally against it – and if I’m against it, I have to do something. That’s why Zoma is a place where your conceived identity is dismissed and you become just human. That’s what I want my legacy to be.”

Unsurprisingly, Zoma is a popular spot

Perhaps the most substantial part of the museum is the organic garden, growing everything from herbs to fruit to flowers, with a particular focus on reviving the country’s endemic plants. As well as being edible and educational, the idea behind it is also that it may provide a respite from the busy city, where green spaces are few and far between. “Finding a place to breathe is really important,” adds Assegued.

Happily, since Zoma began, other sanctuaries like it have popped up around Addis. One such place being Unity Park, which the Zoma team helped Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed to create.

“We love being part of projects like that, because we advocate the importance of understanding and maintaining nature,” explains Assegued. “We believe you have to be friends with the natural world. It’s not even a choice, really – it’s a survival issue.”

Intricate patterns sculpted by Elias Sime

Following the success of Unity Park, the prime minister enlisted them again to create something meaningful with the land at Entoto Park. The result? Zoma Park Village, which will be ready in a year and a half. The large-scale eco-village will include everything from art galleries, a children’s centre, a library and co-working space to a spa area and a wild campsite. There will also be restaurants and a culinary school led by renowned Ethiopian culinary genius Chef Yohanis.

While the outcome of this project will be a fun yet educational tourist destination, for Assegued and Sime the reward particularly comes from what they’ve done to preserve the area’s nature. “We managed to save Entoto from landslides and have transformed the whole forest into indigenous forest, which will attract a lot of birds and other animals,” says Assegued. “Truly, my heart is at Zoma and at first I wanted to get the project finished so I could get back there. But now I’m completely in love with our village at Entoto.”